January 2023 marks the 44th anniversary of the fall of the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia. The Khmer Rouge's regime was brutal, leaving scars that have lasted generations. Liz Coward writes on the early days of the regime's rule and the viciousness with which they held power.

Phnom Penh was one of the first cities to experience the regime’s brutality and Toul Sleng Genocide Museum and Choeung Ek killing field, continue to hold this sadistic organisation to account.

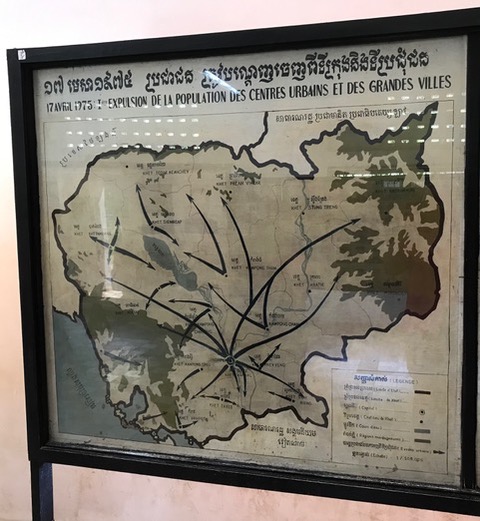

The victorious Khmer Rouge army entered Phnom Penh on 17 April 1975 to the sound of cheers. Refugees and residents celebrated because the civil war had ended, the despised Lon Nol government had been defeated and peace and normality could be restored. However, within hours of arriving, the Khmer Rouge aggressively ordered everyone, including the hospitalised, to leave the city. The discombobulated population was told the Americans were about to strike or that Lol Nol troops were hiding and had to be flushed out. They were told to pack three days’ worth of possessions because they would be returning home soon.

17 April 1975: First expulsion of population of urban centres and major towns (courtesy Liz Coward).

These were lies. The forced exodus to the countryside was permanent for Phnom Penh’s citizens were seen as contemptible ‘new’ people and the source of slave labour required to create the ‘independence-sovereignty’ of the new Democratic Kampuchea. For the next few years, these internally displaced people would live in poor agricultural communities or purpose-built camps where families could be separated and everyone would be indoctrinated, starved, worked to exhaustion and despised by the Khmer Rouge and the superior ‘old’ people, the farmers. Educated people like doctors, lawyers and teachers would be identified and executed.

Over time, paranoia set in within the Khmer Rouge. Subsequently, one of Phnom Penh’s former secondary schools was converted into Toul Sleng Prison, (S21) to deal with those accused of betraying Angkar, the omnipresent, secretive, and faceless organisation which represented the Khmer Rouge.

One of the barbed wire wrapped prison blocks at S21 (courtesy Liz Coward)

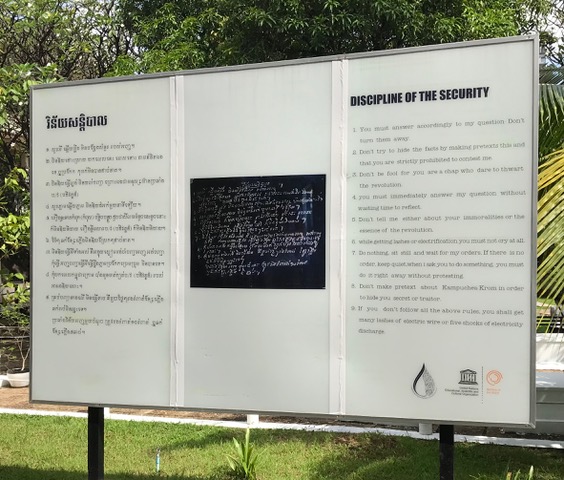

By December 1976, blind-folded and shackled men and women began arriving at S21. In the eyes of the fanatical young guards and interrogators, Angkar was infallible. Therefore the prisoners were traitors and their job was to prove it and weed out more treachery. The stakes were high for failure to gain a confession could result in their own incarceration.

Chum Mey was 47 when he arrived at S21 on 28 October 1978. Although a ‘new’ person, he was a skilled mechanic and had been employed by Kun, a Khmer Rouge chief.

A few weeks prior to Chum’s arrest, Kun himself had disappeared. Suspecting nothing, when Chum was told by some unfamiliar soldiers that he was needed to work near the Vietnamese border, he left with them and ended up at S21.

Like thousands before him, he had no idea why he had been arrested. For 12 days and nights he was interrogated about his connections to the CIA and KGB: “Who introduced you?” “How many were in your group?” Chum Mey had never heard of them, so couldn’t answer. That’s when the beatings stopped and the torture began.

VIP interrogation room at S21 Phnom Penh Cambodia (courtesy Liz Coward)

After 10 days, he gave them what they wanted, a confession that he was a CIA operative working in an extensive network of spies and saboteurs. His ‘network’ consisted of virtually every person with whom he had worked. A list of names was compiled and each one investigated. As time went on the list was updated with comments such as, ‘present unknown,’ ‘arrested and disappeared’ and ‘now arrested’. As anticipated, Chum’s former friends and colleagues soon found themselves at S21 and the familiar cycle of interrogation, torture and confession commenced. The final stage was execution, a fate Chum Mey escaped because he was useful. He could fix the typewriters upon which the confessions were made. Only 12 people survived S21, four of which were children.

Initially the dead were buried behind Toul Sleng Prison. When it ran out of space, a quiet orchard and old Chinese graveyard was found just under 18 kilometres south of Phnom Penh. This became Cheung Ek Killing Field.

Prisoners interrogation rules at S21 (courtesy Liz Coward)

At night, the prisoners could hear the trucks pull up outside S21. Names were called and blindfolds and ropes applied. If they hadn’t already been, children were separated from mothers and husbands from wives. They were then marched out, loaded onto the waiting trucks and driven through Phnom Penh’s deserted streets. They were unaware that their young executioners, men like Him Houy, travelled with them. Eventually the trucks arrived at Choeung Ek. Him Houy explains what happened next.

“We backed the truck up to the hut, lifted the flap and threw them onto the ground. We made them go into the hut. We started the generator inside to deafen them so they wouldn’t hear anything. Then we brought them out one by one.

We took down their names. We said, “Don’t be afraid. You’re going to a new home.” We made the prisoner kneel. His hands were tied behind his back with a kramar over his eyes. We took an iron bar and struck him in the back of the neck. He fell face down. We cut his throat with a knife. Then we removed the hand cuffs. If his clothes weren’t stained, we took them too, but not those stained with blood. We piled the clothes in a corner.

We dragged the body over and threw it in the pit. After the executions we checked the rosters. If prisoners were missing, we had to bring the bodies up and recount them. When it all tallied, we threw them back in the pit and buried them completely.

I got all the handcuffs together and put the clothes in the truck for the other prisoners to wear. We had to hurry to get back before daybreak.” (Him Houy – Security Deputy S21).

One of the 129 mass graves at Choeung Elk killing field. (courtesy Liz Coward)

An estimated 18,000 people were killed at Choeung Ek. The exact figure is unknown because a decision was taken not to unearth all the burial pits, some of which are now submerged below a lake.

There are 390 killing fields and over 20,000 mass grave sites in Cambodia.

Whilst the Khmer Rouge was in power between 17 April 1975 and 7 January 1979, approximately two million Cambodians were killed, died of starvation, preventable diseases or in childbirth. 7 January 2023 marked the 44th anniversary of the regime's fall.

Some of their victims have no known remains. None of the five million survivors was left untouched. The country’s society, culture, religion, industry, government, legal, education and healthcare systems were erased. Shamefully, political expediency triumphed over justice so most of the perpetrators of this appalling genocide returned to their previous lives or died of natural causes.

Banner image: The Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Image: Wikimedia Commons

- Asia Media Centre